Most of this chunk is taken up with a detailed description of a second census of (the men of) Israel, and an easily missed final sentence shows that by this point many years have passed and a whole generation has died off. Clearly the chronology of this record is far from complete - the first few chapters all seemed to occur within months of leaving Egypt, now all of a sudden as much as three or four decades have passed by. From time to time the people have settled here or there, at others they have been embroiled in battles, now, after a rather ugly account of events involving Moabites, a new head count is undertaken.

Word choices

Not being able to read Hbrw (Hebrew), I can't go to the original text here, and my interlinear is at church. But I was struck that the word choices vary quite considerbaly throughout this section.

According to the NRSV (and KJV) "the people" are involved in sexual relations with Moabite women.

In the census we have "the descendents" of Reuben and Simeon, "the children" of Gad and the "sons" of Judah. Issachar and Zebulun have 'descendents', Joseph has "sons". Ephraim, Benjamin, Dan, Asher and Naphthali all have "descendents". The Levites are not numbered, but the clans are listed.

Does this matter in context? I suspect not, but it is interesting to note which words are used because of the way that scripture is then read and interpetted. "The people" or "the descendents" will be heard very differently from "the men" (NIV) or "the sons.

Net Change

The first census numbered a total of 603, 550 men of 'fighting age', by the second census the number had reduced to 601,730. Some tribes had increased, others had decreased. A bit of web searching (as I was too lazy to re-read the first census and do the sums myself turned up this neat summary which shows that, overall, the population was pretty stable (down by 0.3%) whilst inidividual tribes varied considerably, e.g. the tribe Simeon shrank by 63% whilst Mannasseh grew by 64% (I haven't checked the arithmetic, but the order of magnitude is what matters).

Every year assorted Baptist (and other) bodies undertake some sort of census of their churches. The number of congregations, the number of people in formal membership, the number of adults in certain age brackets or of specific ethnic groupings. Sometimes the numbers are up, sometimes they are down... and when they are down, a degree of centralised twitching arises to try to redress this.

Do these numbers matter? Why did Moses collect them? Why do we collect them? For Moses, this second census was linked to allocating chunks of land. For denominations the census sometimes seems to be a bit of a box-ticking exercise (we have N people in category Y) but can also inform priorties.

Surely, though, there has to be a note of caution - any allocation made on numbers is temporal. Populations rise and fall quite naturally. Proportional and absolute changes have different implications. Decisions made on demographics often come back to bite those who make them (the closing, merging, opening and extending of schools across the UK seems to be a prime example of this).

It is useful, I am sure, to have a reasonably accurate picture of the demogaphic of our congregations and denominations... but it's what we do with that information, how it shapes our thinking, that matters... and that it doesn't become an end in itself!

Dividing up the Land

The land is to be divided up using a two-fold approach, by lot and by population. As I read this, I was reminded of an image I'd seen online a week or so back, that expressed the population of London in terms of other UK cities:

The areas are allocated by population, so that the next largest cities in the UK, Birmingham, Leeds, Glasgow have populations equivalent to relatively small areas of London. London has a population broadly similar to the entire county of Yorkshire or the whole nation of Scotland.

I'm not for a nano-second suggesting that these islands could or should be redistributed by population - there are endless reasons why that would be a bad idea - but it is an interesting comparison to make, and it does explain (to me at least) why some of the misunderstandings and injustices (real or perceived) arise. I'd love to see a similar graphic for Glasgow (can't fine one) which, at least population-wise, occupies an equivalent position in Scotland.

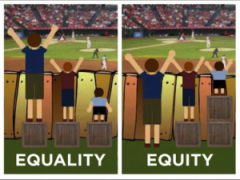

For all the preceding waffle, there is an important question here, I think, which relates to the distribution of resources among the people of a nation. Not all land is equally fertile or productive. Not all people have the same opportunities. Equal is not necessarily equitable. I am also reminded of this graphic:

I have no answers, I just know that it is all incredibly complicated!

Who'd have thought that would emerge from another long list of names and numbers!!