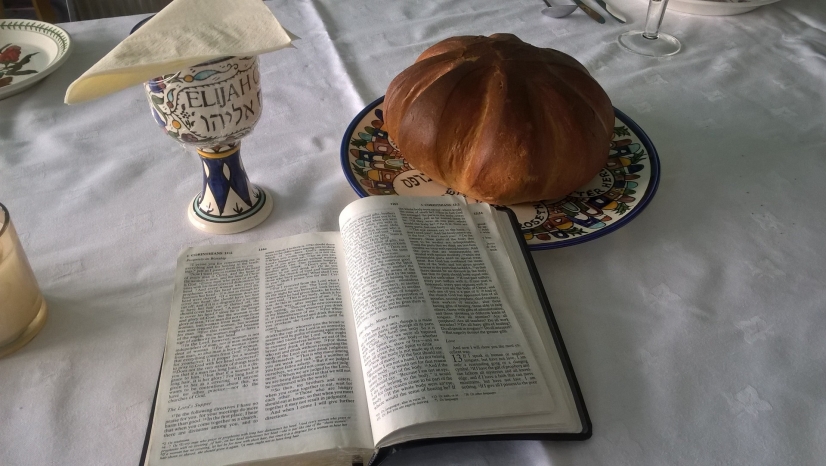

This morning we pondered the letter to Philemon, which was read in conjunction with part of Colossians and with a bit of Galatians as a call to worship.

Paul's dilemma - he espouses a theology of a reconciled creation in which such potentially divisive categories as race, gender and status have no significance, and now he has to deal with the very real issue of a runaway slave. How should he respond?

We looked at four possiblities:

The parable of the starfish method - I can't change the world but I can make a difference in this specific instance (so, not challenging the status quo of slavery but making an empassioned an dpastoral plea on behalf on Onesimus)

The prophet method - to denounce the status quo and announce an alternative... noting that few are truly called to the prophet's role, and for most the task is to hear and respond

The subversive method - obeying the rules to the letter in a way that shows how ricidulous they are: turning the other cheek, giving your tunic as well as your cloak, walking the extra mile

The transformative method - being salt and light, or the leaven in the lump , or the mustard seed. Values and actions that influence those nearby subtly and significantly, changing culture and practice.

What we need to do is - hold on to our vision of a renewed, reconciled creation and by whatever means is right for us, starfish, prophetic, subversive, transformative or any blend thereof, live out what it is we profess.

And that is my sermon in a fraction of the words!!